After leaving the boat in Cowes for a few days for the force sevens to blow over (see previous post) we returned still undecided about where to go: south to the Channel Islands and down to St Malo? But it’s already the French holiday season, the English one is starting and there’ll be packed moorings and marinas everywhere, plus the new customs and immigration bureaucracy.

Furthermore, it looks from the forecast as if the first three days after arriving will be spent sheltering somewhere. After that we’ll be worrying about finding a weather window to get back to Cowes a few days later.

The answer, we decided, was to follow the wind east and head for the Thames Estuary and Suffolk.

A big advantage, apart from it being a pleasant and relatively uncrowded cruising ground, is that it’s reasonably cheap and easy to leave the boat there and go back for it later. That seemed a good plan given the likelihood that the current string of lows will keep coming in from the Atlantic for the next few weeks (forced our way by the heat dome over the Mediterranean). A summer mooring on the east coast for a month can be rented for the cost of a week in most places on the south coast. So Suffolk it was.

We set off motor-sailing down the Solent at 6am with a light wind on the starboard quarter, heading for the passage through the Owers at Selsey Bill. The engine was soon off as the wind gradually built up over the day to a south-westerly 4 and occasionally 5. We reached Beachy Head 60 miles away well before dusk, then passed outside the Royal Sovereign shoal to stay away from the inshore route in the dark – there are large numbers of unmarked pot boys near the shore.

We passed Dungeness, and at Dover were not only dodging ferries but also a dozen small boats crawling south in a compact fleet, all in the same direction, at less than 2 knots – a puzzling sight, because they were lit up like a crowd of fairy lights bobbing on the sea.

I thought at first it was amateur sea fishermen working in company, but the coastguard then gave us the answer. They called us by name (we had AIS and AIT on) and asked us to give the boats as wide a berth as we could: they were cross-channel swimmers heading for France, each with their individual escort boat.

Spotlights on the swimmers from the boats gave us an occasional glimpse of a head or arm as we moved closer and steered cautiously between them. The fleet was too spread out to go behind it without moving closer to the Dover ferry entrance than was safe. It was 3am, but there were still several ferries entering and leaving during the time we were passing the port.

We had been looking out for refugee boats heading in the other direction – the coastguard put out general requests to report their positions if seen – but we did not come across any, though it was the right sort of weather for them. The refugees would have wondered what on earth was happening if they’d run into the fleet of swimmers and their escorts.

Dawn came after we had threaded our way through the Gull Stream passage between the notorious Goodwin Sands and the shore. It was daylight as we passed North Foreland, beating up against a north wind to the marked channel through the London Array windfarm in the Thames Estuary.

The huge windfarm is built on Long Sand, a bank stretching way out into the north sea. The farm site runs spectacularly across the Foulgers Gat small craft passage which cuts through Long Sand into Black Deep, one of the main east-west shipping channels in and out of the Thames.

After passing through the Gat into Black Deep we decided against the shallow Little Sunk short cut because it was low tide, and went round the north-east end of the Sunk sand. We then headed across the end of the Gunfleet sand and the Wallet inshore channel towards the shallow Medusa Channel, which bypasses the Cork Sand that shelters Harwich. The Medusa Channel cuts up inshore past Walton on the Naze to Harwich.

Finally, we entered Harwich Harbour and passed the enormous container ships on the Felixstowe side, motor sailed up the River Orwell past Pin Mill, and settled down comfortably for supper on board – and a rest – at Woolverstone Marina, in sight of the Orwell Bridge at Ipswich. The three of us had brought Spring Fever 180 miles from Cowes in 34 hours.

We spent three nights at Woolverstone, exploring locally and meeting old friend Charles for lunch at Pin Mill. Sadly, the marina’s restaurant and cafe is closed after a fire, though the Royal Harwich Yacht Club next door serves food and drink to marina customers. We then set off 12 miles for the River Deben.

The entrance to the river has changed dramatically this year, moving hundreds of metres north by opening a new, narrow gap in a sand and gravel bank. We had downloaded the new Imray chart of the entrance from http://www.eastcoastpilot.com and we also phoned Mr White, the pilot and harbourmaster, to check whether anything had changed since the chart was published in the spring.

At Ramsholt, George, the harbourmaster, has retired and when we asked his successor how much it was for a night on a mooring he replied that they don’t charge any more – the first free mooring we’ve come across for a long time. The Ramsholt Arms, opposite the mooring we borrowed, is one of the nicest shore-side pubs anywhere; we met Caroline there for lunch the next day.

The weather continued unstable, with brief days, and sometimes just hours, of sun and warmth, interspersed with rain and strong winds. So we left Spring Fever on a swinging mooring at Woolverstone and will take her back to Cowes when the forecast improves.

Shifting sands

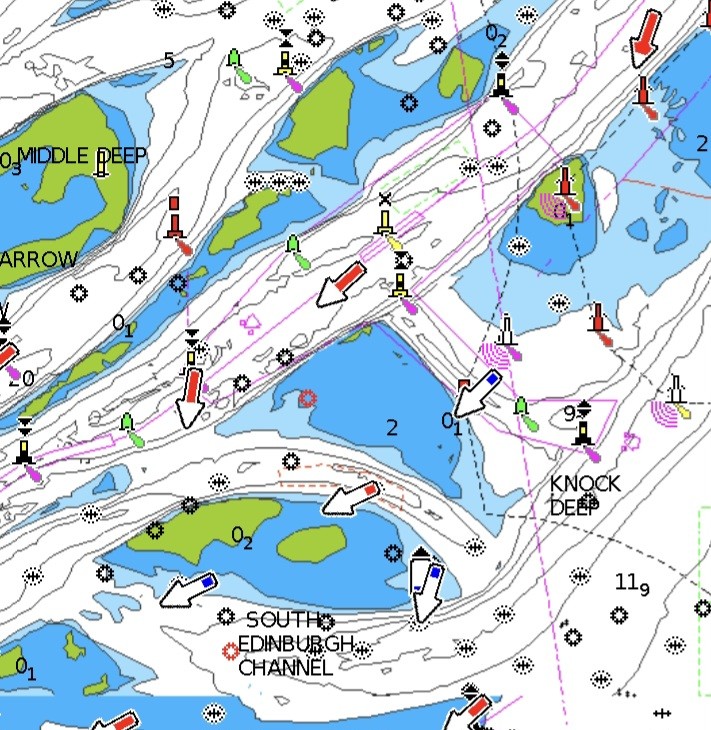

The whole area of sandbanks has changed dramatically since I first crossed it, as tides and storms move vast quantities of sand. Ships going south used to be sent through the Edinburgh Channel at the west end of Long Sand. Yachts and fishing boats were advised to use the shallow and badly marked Fisherman’s Gat passage further east, across the sand.

But the Edinburgh Channel filled up and is now a shallow and unbuoyed swatchway, as minor passages through the sands are called. The main ship channel is through the previously shallow small craft short cut, Fisherman’s Gat, which is now deep and buoyed.

Since the changes, small craft have been advised to go instead through Foulgers Gat, which used to be shallow, unmarked and hard to find. Once the wind farm was built across it, the whole area became lit up at night like Christmas trees and so is easily passable in the dark, which would once have been rather foolish. Three red and white safe water buoys were installed to make the route easier to follow, though it’s still shallow.

In principle, windfarms are open throughout to navigation as long as you keep more than 50 metres from each giant tower. The lowest point the arms reach is tens of metres above our 14 meter mast. But the London Array windmills are all built on a sandbank, and sand is accumulating around them, so we’ll leave wandering around the rest of it to fishermen in shallow draft boats.

There have been many more changes in the estuary in the years since I first crossed it. The latest is silting up of Middle Sunk, one of the swatchways for small craft across the Sunk, a bank parallel to Long Sand that also stretches for miles. Now only South-West Sunk and Little Sunk are safe crossings.

However, the Medusa Channel up to Harwich has a long history which suggests its bottom is unusually stable for the east coast. It’s called Medusa after a ship captained by Lord Nelson, who took a big risk by slipping out that way into the north sea when the wind was preventing the rest of the navy from leaving Harwich by the deeper main entrance.

L