Another important factor in keeping tiredness down is comfort. It starts with the best breathable waterproof clothing in multiple layers that are easy to remove and which minimise condensation. Feeling comfortable is not directly a work saver, but makes everything less tiring.

Related to that is warmth, especially comfort at anchor. With no heating, anchoring in cold weather means damp evenings in full thermals and jackets, and unpleasant crawls into freezing sleeping bags. When Spring Fever’s ancient Eberspacher diesel heater is occasionally working, she’s snug and cosy down below.

Unfortunately, it’s been unreliable for years, so warmth has been a question of luck – will it, won’t it work? A local specialist, Paul Carr of Cowes Marine Electrical, has looked at it and says it’s time for a new one. We’ve ordered a Teknotherm 4kw model. It’s a lot of money, but in British waters there can be four seasons in a day…

Effort-free food on passage is also a great help. There was a time when we made it a point of pride to cook at sea, even if it was only re-heating vacuum packed stews. An owner I raced with insisted on full English breakfasts every day; fine for some, but it could turn others green. On our passages of 48 hours maximum, we take ready-made supermarket sandwiches, apples and energy bars, and drink water with the occasional hot coffee and tea. (We won’t go as far as Ted Heath, the sailing Prime Minister, who was reputed to feed his racing crews entirely on Mars bars).

Getting navigation right is vital in an era when paper charts are rapidly disappearing. This link takes you to a detailed account of how we renewed our navigation electronics and installed multiple chartplotter backups at relatively modest cost.

A good autopilot is an extra crew member, taking over work on the wheel for long periods. It can’t cope with the worst weather, but most of the time it’s a great help. We’ll have our 4 year old Raymarine wheelpilot checked over.

Our sail-handling gear is pretty good for lazy sailors, after a lot of modifications, but could do with one minor refinement. The halyards, reefing lines and other sail control ropes are already led back to the cockpit through rope clutches to the winches under the sprayhood, to minimise the number of times we have to struggle along the deck at sea. We also run the preventers for downwind sailing back to cockpit winches before we set off.

The extra refinement: we’ll set up a cunningham downhaul from the luff of the mainsail and run its control line back to the cockpit winches. A cunningham pulls the bottom foot or so of the mainsail luff towards the boom. It flattens the sail as the wind gets up, with far less effort than winching the halyard.

We need a big enough dinghy. We have struggled for years with a 2.4 metre lightweight Plastimo bought to fit in the cockpit locker of the previous much smaller boat. It feels overloaded with two large people in it and is a challenge to get into. This winter we bought a 2.7 metre dinghy to replace it. The extra size and buoyancy, with bigger tubes, will make getting ashore a much more enticing thought. It’s the same size as the Zodiac we had before the Plastimo, which is fondly remembered because it was so much easier to use.

We ought to mention the gear we know we need but which is beyond this year’s budget. Anchoring is hardwork and perilous for the ageing back, as a friend found when hauling up the anchor cost him a crushed vertebra and six months of pain. We have a 15kg main anchor, 30 metres of chain and 50 metres of rope, about as much as you can put in the anchor well of a 36 foot hull designed for racing, without sailing head down and digging into waves. Unfortunately, we still have only a manual anchor winch. A proper installation of an electric version would set us back more than £2,000. It would be sensible to have, but not now – the heater wins.

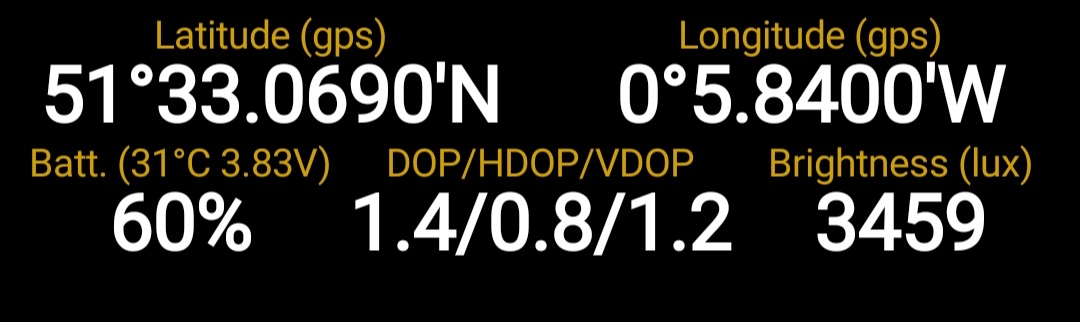

navigation. In the era before modern electronics, when everything had to be done at the chart table, it was tough going up and down regularly to write log entries, update our chart position and – in far distant days – take a bearing with a nausea-inducing radio direction finder. In rough weather and at night it quickly became seriously exhausting. A great energy saver arrived when we first put a chartplotter in the cockpit, so we were not obliged to struggle down to the chart table and back again every time the log had to be entered or the chart checked. If the weather and sea are making us work hard, we keep a deck log instead in a notebook and enter it later.But we’re out of date. The reliable though ancient Standard Horizon plotter, mounted in front of the wheel, has complex buttons and a tiny screen which is difficult to read with tired eyes, especially at night, and it’s tricky to programme quickly with revised routes while at sea. More problematic still, its charts can no longer be updated. So we are about to fit a modern Raymarine Element chartplotter to make it easier. More details here of our electronic navigation equipment (including Raymarine and Digital Yacht, plus Memory Map, Marine Navigator, VMH and Antares charts).

As mentioned in the post Lazy Sailing for Oldies, we are about to replace our reliable but ancient Standard Horizon plotter with a new Raymarine Element 7S. This has a modest 7 inch screen, but that’s big enough, because it will be at eye level immediately in front of and above the wheel.

We deliberately avoided the fancy touch screen models that they sell most of nowadays. The feedback we got from users on line and in conversation was that if you sail in an open cockpit in wet and windy places, a touch screen is the last thing you want: even the allegedly improved recent versions behave eccentrically when they’re wet.

Element also happens to be Raymarine’s cheapest range, marketed more to amateur fishermen than to yachts. A dealer we spoke to said simple button-controlled devices like Element and other equivalents remained the best bet for sailing yachts with open cockpits, even though they were mainly marketed to fishermen as fishfinders.

There are also models with both touch screen and button control, but they are twice as expensive – and three times the price we eventually paid Force Four chandlery in a sale for our ex-display Raymarine.

The Element and the pricier touch screen models are all Multi-Function Displays (MFD). Even ours at the cheap end will show AIS, radar, depth, wind, log and engine and fishfinder data on split screens. Of those, we only want AIS signals showing ship location.

There is no way of connecting our ancient radar, the other instruments would probably have to be upgraded if we wanted to integrate them, there’s no point in having a fishfinder, and the engine control panel would have to be renewed to make it talk to an MFD.

We have a Digital Yacht AIS transponder from 2010 which still works well, broadcasting our course details on VHF as well as receiving ship positions, course and other data. It uses an old communications standard called NMEA 0183.

To link it to the new plotter we bought a Digital Yacht device called iKonvert which changes the signal to the modern NMEA 2000 standard. We also bought the simplest possible Digital Yacht starter kit for the highly specialised cabling and connectors needed for NMEA 2000. The total cost was well under £300 against a starting price of about £750, plus the cabling kit, for a new AIS.

For £5, we’re raising the AIS aerial 2 metres above the rail where it is now, by strapping a length of grey plastic plumbing pipe to the pushpit rails behind the helm, rather than the pricey stainless steel tube that’s often favoured. That will increase the range at which we receive ship positions.

Our old plotter was mounted flush on a glass fibre pod immediately forward of the wheel. We’ll make the new one removable by putting it on a Raymarine bracket fixed to the old pod. It can be easily released from the bracket.

That way it can be protected down below when we’re not on board and taken home in the winter to update and add routes. The old plotter has been fixed solidly in the cockpit ever since it was bought.

We’re old fashioned – we don’t like the idea of having all our navigation instruments linked together in one display. We like lots of redundancy, as they say in the systems world – if one device goes down, we want multiple independent backups.

That’s why we also have two tablet chartplotters. One is an 8 inch waterproof, shockproof and sunlight-readable Samsung Active 2 T-395, which can be used in the cockpit; the other is a 10.5 inch Samsung tablet mounted at the chart table.

In fact, if things really get difficult, we have mobile phones on board with the Navionics chart app loaded, and it’s perfectly possible to do basic navigation with either of them. Navionics subscriptions can be used on multiple devices. If the boat’s batteries fail, we have several spare rechargeable batteries for the tablets and phones, including a large dual purpose one which can be used as a jump starter for the engine when the main batteries are flat or for topping up tablets and phones.

Charts

We have slashed the number of paper charts on board, which is why we focus so much on backups for our electronic charts. Reliablity of electronics will become increasingly important because the UKHO is set to phase out all Admiralty paper chart production from 2030 (delayed from 2026 after protests). Only Imray has promised to carry on publishing paper charts.

A full set to go round Britain in the old days could involve a hundred or more Admiralty paper charts, because lots of inshore detail is needed (there are 850 for the whole of the UK and Ireland). On both Round Britains in 2007-8 and 2012-13 we did not want the cost of a full set of paper charts, and even less did we want to spend the time required to update them.

Instead we relied on our chartplotter plus Imray paper charts for yachts, which cover long stretches of coast, with detailed inserts showing ports and estuaries. There are, for example, only 6 needed between Harwich and Oban, which is half the round-Britain distance.

On the first round Britain we were chancing it a bit, because we did not have tablet or phone back up to the plotter, even though we had the bare minimum of paper charts. The second time we took a laptop as backup, but that’s cumbersome and needed a lot of power to charge from a 12 V boat system.

Nowadays, we are much more serious about electronic backups. Yes, a lightning strike could knock it all out – but hopefully we will have remembered in time to put one of the tablets in the oven! Steel all around shields from high voltage.

Our old plotter used C-Map vector charts, which are good, with lots of extra information beyond the basic chart data, accessible by clicking on chart features. This is the basic advantage of the vector type, which are also multi-layered and show more detail as you go deeper. C-Map is good but Navionics vector charts are cheaper, more flexible when used on tablets, and much easier to update, so we have switched to those.

We have reservations about Navionics accuracy from past experience. So it is reassuring to add multiple electronic chart brands, each with their own advantages, so we can crosscheck.

On the tablets we have the Memory Map app with Admiralty-based charts – the gold standard – loaded for the whole of the UK and Ireland, all 850 of them. They are the raster type, which look exactly like paper charts. They show detailed hydrographic survey information in their notes sections. That gives an indication of chart reliability which is missing on vector charts for leisure users. Unlike vector charts, raster charts do not show more detail as you enlarge them.

Both the tablets also have the wonderfully detailed Antares charts of anchorages on the West Coast of Scotland, produced by Bob Bradfield, which make up for the serious deficiencies of all other charts close inshore in Scotland, including the official Admiralty ones.

Finally, the cockpit tablet has an excellent app called Marine Navigator, with the 850 Admiralty-based charts for the UK and Ireland supplied online by VMH of Cowes. It is a more clearly presented version of Admiralty charts than Memory Map, and the Marine Navigator app has much better navigation functions. Antares does not work as well as on Memory Map, but we have loaded it nonetheless. We will have Navionics, Admiralty and Antares available on both tablets.

Memory Map, Antares and VMH charts and their apps are a small fraction of the price of buying Navionics and other brands for a full-function chartplotter. At £60 the lot, it’s no great financial burden to add them all as backup. The waterproof tablet, the Samsung Active2, cost £75 second hand on backmarket.co.uk. The other Samsung is a second-hand 10.5-inch model bought two years ago for £125 from Backmarket.

There is one advantage of Navionics that is new for us: we can load routes from the tablets or the phones to the chartplotter and vice versa, so we can follow the route both at the wheel and at the chart table. Routes are prepared in advance on the tablet and copied onto the plotter.

They are first saved as GPX files onto the tablet’s SD card. (GPX is a type of file widely used in land mapping). The chart card on the plotter is removed, the SD card is inserted in its place and the GPX files saved to the plotter’s memory. The SD card then goes back to the tablet, and the Navionics chart card is reinserted in the plotter. Transferring routes to the tablet from the plotter reverses the process.

Raymarine’s own chart brand, Lighthouse, allows direct transfer of GPX files from tablet to plotter using a local wifi generated by the plotter, and more expensive plotters – way beyond our budget – will mirror their screens directly to a tablet. We prefer Navionics, because it is so flexible on tablets and phones, even if it is restricted to SD card transfers