This year’s race from Venice to Novigrad and back felt like two different events. The first leg outwards was a hard-working disappointment, while the return home was a fast and enjoyable sail in mostly fine weather that more than made up for the earlier frustrations.

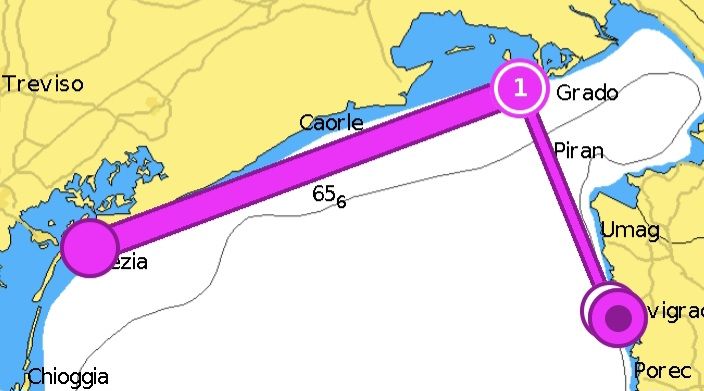

On the way out to Novigrad, only three boats out of 30 entrants managed to finish the overnight race, and everyone else withdrew part way through. The challenges that defeated most of the fleet were a combination of a north-east wind, a change in the course and the gradual then complete disappearance of the wind not long after dawn.

The first problem was nothing out of the ordinary in a race: the wind was coming from roughly the direction of the first turning mark, so it was a beat to windward all the way. Some boats made short tacks close to the shore; others, including us, started with one long tack to get further out and find stronger winds, which varied from Force 3 to brief periods of Force 5, complicated by a nasty little chop in the shallow water.

That’s no big deal, but it was what happened next that ended the race for so many boats: the wind dropped to almost nothing by the time the bulk of the fleet closed the turning mark near Grado, and so there was no chance of getting down the 22 miles south to Novigrad by the 1600 cut-off time.

The problem was compounded by the race committee’s decision to add 9 miles to the windward leg along the Italian shore, making it 41 miles, right to the edge of the Gulf of Trieste. The extra 9 miles* was what did most to scupper peoples’ chances of finishing. It’s a handicap race, and only a handful of big yachts with expensive laminate sails had the speed to get close to Novigrad before the wind died.

Many of us, especially the smaller boats, retired well before the beacon, once it was obvious that we’d never finish by 16.00.

We motored the rest of the way, slowly in the case of Spiuma, because her lagoon friendly electric motor eats up battery power when driven too hard. Several skippers gave up altogether and turned north to ports on the Italian shore, leaving empty tables in the restaurant reserved for race crews on the seafront at Novigrad.

The frustrations were forgotten once we settled down for dinner on a sunlit terrace in the delightful little resort, later watching the sun set while we sipped our coffee.

We were a crew of three – skipper Martin, myself, and son Will, who has been living with his family in Venice. Will’s Italian family – Faye, daughter Indigo, grandmother Lucia – were on holiday in Istria less than an hour’s drive down the coast, and they joined us for dinner. The next day we lunched at a restaurant among the pines, swam in the warm water of the bay and played mini-golf, while Martin went on a vineyard tour to buy a case of delicious Istrian white wine, a malvasia with a hint of saltiness from vines growing near the shore.

The race home started later that day, at 20.00, from a line just outside the harbour. This time, the wind was a steady Force 4 from behind. Spiuma does not have a spinnaker, which is vital for fast sailing when the wind is coming from right behind the boat. So instead we steered 30 degrees away from the line of the course on a reach, always the fastest point of sailing, knowing that the wind was forecast to move from south round to east later in the night. When it did exactly that, we were able to gybe the sail on to the other side, and continue on another fast reach direct to the beacon.

Though we sailed further than the direct course, we got there a lot faster than if we had pointed directly downwind all the time.

As we neared the beacon, we watched a spectacular electric storm in the sky, which happened to be exactly above a big fireworks display marking the end of a festival day at Caorle, a town on the coast. Great starbursts of aerial pyrotechnics rose into the sky as streaks of lightning came down from the clouds and thunder rolled, accompanied by the staccato bangs of giant fireworks. The thundercloud was side-lit by the glow of a half moon away to the west.

After we rounded the beacon and headed for home, we were back to the same conditions as at the start, with the wind right behind us. So we employed the same tactic of reaching away from the line of the course and gybing back.

Later, we went under the almost stationary thunder cloud, with the wind rising to a gusty Force 6 for half an hour. But that was accompanied by a wind shift to north, so we were at last able to sail directly towards the finish, relaxing and breakfasting as the wind eased and the sun came up.

It was a perfect sail in the sun for a few hours, until the wind began to die again when we were only 4 miles from the finish. Thankfully, it did not completely disappear, so we were able to coax Spiuma gently through the zephyrs to the finishing line at just after 11.00 am. She has nearly always been the smallest boat in the race, and often gets a special prize just for finishing. When the results came in, we were third out of six in our class.

This was my sixth Transadriatica, and every one has been different. There have been steady breezes, strong gusty winds, calms, rain, blazing heat, a rare cold night or two – you can never be quite sure in advance, because the northern Adriatic is close to mountains and the weather can be volatile, even in summer. But the water is warm and the sun is rarely missing for long, the DVV is friendly and welcoming, there’s always a good dinner to be had in Novigrad – and the race starts and ends in Venice. I can be tempted by warm Adriatic racing, but don’t ever ask me to race again in the English Channel….

*In many EU countries, boats are licensed to sail up to a specific distance from shore, which is set according to their equipment. It seems the extra 9 miles is the result of an instruction that the course must stay within 6 miles of the Italian and Croatian shores. The background is that earlier this year, the organising yacht club, Diporto Velico Veneziano, was informed by the Croatian authorities that only boats with formal registration papers from their country of origin could compete. Catch 22: Italy has no registration system for boats under 10 metres, which meant that many members of the club could no longer compete in the Transasdriatica. The details of what happened next are not clear, but it seems that observing a 6 mile rule is part of a deal under which the Croatian authorities relented and allowed boats under 10 metres such as Spiuma to race there.

One thought on “Transadriatica 2024”