On an Ionian holiday a few years ago, I walked straight off a modern cruising yacht into an argument about an ancient voyage that has been unresolved for well over 2,000 years. We had moored at Vathi, the main town on Ithaca, where in a first floor room down a side street I came across an exhibition of photographs of Homeric sites on the island. There I fell into conversation with a white-haired, distinguished looking man who described himself as director of the archaeological excavations on Ithaca.

Naturally, we got onto the Odysseus connection, for the exhibition was designed to connect present day sites on the island with the wanderings of Homer’s bronze-age hero. I had just read in Rod Heikell’s Ionian pilot book that the island of Levkas, a few miles to the north, had been put forward by some as the true Ithaca. What did the director think of that?

It was as if I had insulted his family, his religion and his country all at once. He exploded. My ears were pinned back for 20 minutes while he set out why the Levkas claim arose from a complete misunderstanding of how ancient galleys were navigated; it was an outrageous attempt to divert tourists to the other island, prompted originally by bad philology and bad archaeology in the late 19th and early 20th century, and anyway the Levkas theory had been discredited as long ago as the 1930s: it was irresponsible for serious authors to reproduce such falsehoods. (1)

I managed to get in another Heikell-inspired question while he paused for breath: how can the modern Ithaca be Odysseus’ home when Homer says that it was the outermost or furthermost island (there are many versions of the translation), which today’s Ithaca quite clearly is not? Levkas and Cephalonia extend further to the west and therefore to seaward of Ithaca.

By way of background, the director said the scandalous attempt to discredit Ithaca had begun when two philologists in the 1890s had proposed Levkas as the island called Ithaca on the basis of Homer’s description of its position. But they were ignorant of what a sailor in those days would have understood by the words furthermost or outermost. The route from the Peloponnese in small craft such as the early Greek galleys was to cross from near Olympia on the mainland to the island of Zakinthos, up the coast of Cephalonia and across to Ithaca, which was therefore the furthermost island on a route used by coastal sailors right up to the 19th century.

The seasonal variation in the direction of the setting sun may have contributed to the geographical confusion, because voyages were undertaken mainly in the summer; the north-westerly heading towards Ithaca would be towards the setting sun at that time of year, which could be synonymous with westwards for a sailor with no other measure of the direction. (2) Levkas itself was not even an island at the time, which ruled it out anyway. The canal separating Levkas from the mainland was dug long after the time of Odysseus.

Mistaken or not, the theory that Ithaca was actually the modern Levkas was subsequently taken up by the German archaeologist Wilhelm Dorpfeld (more famous for his work with Schliemann in discovering the remains of Troy, by taking Homer’s descriptions seriously), who argued that he had found evidence on Levkas of settlement by Mycenaeans, the main Greek culture of the period of the story. There were no remains of the period on the present Ithaca, so there could be no connection, Dorpfeld claimed.

The director said that during the 1930s, the last decade of Dorpfeld’s life (he died and was buried on Levkas in 1940) British archaeologists actually found plenty of evidence to the contrary, including Mycenaean pottery. The Levkas theory was dropped. However, it had been revived more recently by what the director darkly called “amateurs”, some of whom have also suggested Cephalonia as the home of Odysseus. That was the point at which he accused rival islanders of making up stories to steal Ithaca’s tourists.

The director then revealed his trump card: the most convincing evidence in favour of the present Ithaca was the discovery in the current excavations of Mycenaean era coins with the head of Odysseus, proving that people of the time remembered that he came from there.

Forward to 2011, when I joined a friend’s 3 month cruise from Venice to Istanbul, staying for the leg from Brindisi through the Ionian and round the Peloponnese to the eastern side of Atttica. Spurred by that conversation in Vathi, I was much better prepared for the Homeric sites that we would be passing. In fact, it was something of an all-round history cruise, because Martin, the skipper, was fascinated by Venetian history, and planned to visit as many of its settlements and fortresses as he could between Venice and Asia Minor, as well as Homeric sites, including Ithaca and Troy.

One of the books I brought with me was a Penguin Classics copy of a second century tourist guide to Greece by a celebrated writer called Pausanias, parts of which, such as the section on Olympia, are really quite useful as a guide today. The introduction by the translator, Peter Levi, says that as a young man Pausanias “seems to have been an expert on Homeric questions, but the bitterness and malice of scholars in the field drove him to abandon literary criticism”. (3)

Not much has changed over 2,000 years. There have been strident disagreements since classical times about where Odysseus went; one authority has logged 70 different versions of his itinerary (4). Even among modern sailors, books have appeared claiming the authenticity of wildly different routes in the Mediterranean. In cruises on his yacht between 1950 and 1960, Ernle Bradford (5) claimed Odysseus travelled as far as Gibraltar, Libya and Sicily, taking in the Aegean and the central and Western Mediterranean. In 1985, Tim Severin (6) sailed a completely different track in a replica bronze age galley from Troy in Asia Minor to the Peloponnese, Crete and up into the Ionian, claiming – like Bradford – to have found all the key locations but in a far smaller area.

Set against the many confident claims made over the centuries for Odysseus’ landing sites, there is also a long history of scholarship that denies any geographical truth at all in the stories, seeing them as myth (7); yet another school believes that part is myth and part may be based on geographical and historical facts transmitted with varying degrees of imprecision; another sees it as including real settings for a fantasy story, rather like Kings Cross Station’s role in Harry Potter. These strands of debate date back several hundred years BC.

For those in the camp that believed the story had some geographical truth to it, the site of Ithaca was one of the less controversial identifications. Strabo wrote in the first century AD that Ithaca was the home of Odysseus, which was widely accepted; as far as I can tell, the canvassing of nearby alternative islands has been in modern times, when claims began to be made that somehow the island we were visiting had wrongly assumed the ancient name of one of its neighbours.

Cephalonia’s claim

It wasn’t just a Levkas issue. A little online research had shown that the director’s warning about the other “false” claim of Cephalonia to be Odysseus’ home must have been prompted by yet another controversy that was brewing in the world of Homeric scholars. An author called Robert Bittlestone had got into his head that ancient Ithaca was really a long, narrow peninsular on the West side of Cephalonia, and that in Homeric times it had been a separate island.

This is a far from implausible claim, because Cephalonia is in one of the most seismically active areas in the world; the African and European continental plates meet just off the coast of the island, where the water is 3,000 metres deep less than 5 miles out. All the Ionian islands have been plagued with powerful earthquakes, most recently Cephalonia in 1953.

The Bittlestone theory is that the channel between Cephalonia and ancient Ithaca, now the Paliki peninsula, has been filled by upward earth movements and rock falls from the mountain above. He believes the position of the one-time island fits the text of the Odyssey much better, matches a description by Strabo, and its geography is closer to Homer’s description. (8) Somewhere along the line, the modern Ithaca had switched from its Homeric-era name of Doulichion; long periods of depopulation in the Ionian islands after severe earthquakes were a possible reason for the disappearance of the old name and the mistaken assumption later of a neighbour’s lost name.

Bittlestone is no lonely eccentric. His researches were encouraged by James Underhill, professor of Stratigraphy at Edinburgh University, and James Diggle, professor of Latin and Greek at Cambridge, who are listed as co-authors of Odysseus Unbound, the book of the theory, published in 2005 by Cambridge University Press. Bittlestone later raised money to drill boreholes on the island to search for physical evidence and published preliminary findings on his website in early 2012. This is a link to it.

Naturally, I checked what others were saying about Bittlestone on the web. True to form in this contentious area of study, the first thing I found was an English and Greek dual language website that seemed to be based in Athens, much of whose English content was a vituperative attack on Bittlestone and on the Cambridge University Press for lowering its standards by publishing his book. I had to buy it, a heavy hardback volume of 600 pages.

We had a placid cruise down to the central Ionian, preoccupied with finding swimming places and restaurants. We first tried sailing direct to the west coast of Cephalonia to explore Bittlestone’s version of Ithaca, mooring at the lovely village of Assos.

After a swim and lunch, a sudden violent wind blew up and threw us right out of the anchorage, with the anchor dragging so fast that it was eventually dangling vertically from its chain in deep water.

We decided to leave western Cephalonia to find shelter in the little harbour of Kioni at the Northern end of Ithaca, where the next day we hired a taxi, which took us to one of the recent excavations, the remains of an ancient fortified settlement (or perhaps palace) perched spectacularly at the top of a hill. The driver called it the ‘School of Homer’ but it seems to be the place referred to in 2011 news reports of the discovery of a Mycenaean palace.

The archaeologists were away and the site unfenced, so we wandered around as the only visitors.

To discover more, we headed to Vathi and its museum, and sought out the curator. The director of excavation’s inside information about new Mycenaean finds was very quickly confirmed: the curator said the museum should by now have had an exhibition of gold and other Mycenaean artefacts found in recent excavations of Mycenaean period settlements on the island.

There were some amazing things, she claimed, but sadly we would have to wait to see them: the Greek financial crisis had cut off the funding for a new extension to display them, and all was now in store.

Here is a link to a Daily Telegraph report on the Ithaca discoveries. Professor Thanassis Papadopoulos of the University of Ioannina was in charge. (The Telegraph has muddled the Mycenaean era of the Odyssey story – in the bronze age, 1200 BC or before – with Homer’s dates perhaps 300 to 400 years later).

When we got back to the boat at Kioni, we were hit by yet more violent weather: the tiny harbour was being blasted by squalls falling off the hills. The anchor was dragging; we laid a second, and that dragged too, so we abandoned our restaurant reservation and anchored again outside, downwind of the harbour wall, with a long line back to a bollard, to keep us stern to the blasts. After riding out a fierce night with a two person anchor watch, we left at dawn for Ayos Efemia, a harbour on the eastern side of Cephalonia, planning to visit the huge Venetian fortress at Assos, where the bad weather had interrupted us earlier, and then to explore Bittlestone country by car the next day.

The road south from Assos gave splendid views of the northern end of the Paliki peninsular, Bittlestone’s candidate for ancient Ithaka.

We found a road that went through the neck of land between the Paliki peninsular and the mountainous area it faces on Cephalonia, roughly where the channel separating the two should have been. At first, the lie of the land looked right. It was easy to imagine a long inlet over the low-lying farmland. However, the land gradually rose as we drove south towards the Bay of Argostoli, a problem that Bittlestone confronts head on in his book: if there was a channel through there, it is concealed beneath land that now rises to 180 metres, making it difficult for a casual visitor to see how Paliki could have been separate as recently in geological terms as 3,200 years ago. The book, however, goes into great detail about why this is a real possibility.

We didn’t seriously expect to be convinced one way or the other on the geological arguments by a casual visit, so we drove off westwards to see one of the Homeric sites claimed by Bittlestone to be on Paliki: Atheras Bay, which he identifies as where Odysseus landed after his travels. It is a small bay at the head of a much larger one. Bittlestone goes into great detail about this and the other Homeric sites he has identified on Paliki. Whether or not one buys the idea as a whole, Atheras, a serene and beautiful place, would make sense as a sheltered landing for craft that must be beached. It is on the far north-west of the Paliki peninsula.

From there, we went looking for lunch; after a detour round a steep, narrow road, we located a tiny village and harbour a mile or two to the east, on the same coast, where there was a small, informal restaurant that served large quantities of fried sardines with chips, salad and beer, one of those meals that are perfect in their setting.

Over lunch, we debated whether our visit had cast any light on the disputes about Ithaca. The mood of the lunch, as it were, was that Bittlestone had a lot more to prove, especially about the huge changes that he believes filled in the claimed channel between Paliki and Cephalonia; the land now rises to such a height that only a cataclysmic ground shift and perhaps the closing of a spectacularly narrow and deep gorge between the two islands could explain such a big change.

I am also put off by the degree of precision in Bittlestone’s identifications of a whole series of Homeric sites on the peninsular and around the Bay of Argostoli; it reminded me of the overly-confident assertions about locations in the contradictory versions of Odysseus’ travels in the Bradford and Severin books, and there was the same degree of unproven assertion in the identification of many of the Homeric sites on modern Ithaca. The guidebooks, of course, pick up the suggested locations, and the tourist buses take you to them, but most are completely spurious.

Oral history is fascinating, and I’m instinctively sympathetic to the idea that the name of Odysseus’ homeland has endured on its original island for more than 3,000 years. It would be wonderful if that were true. Maybe the director has won the argument with his excavations? I’m not sure anyone has yet, or ever will conclusively.

Peloponnese stories

We learnt a little more about the nature of these arguments when we left the Ionian and sailed round the Peloponnese, visiting Olympia (via the harbour of Katakolon) and then a series of great Venetian, Ottoman and Frankish fortresses on Martin’s list, together with two places that are important in the Odyssey, Pylos in the Bay of Navarino on the west coast and and Cape Malea at the southern tip.

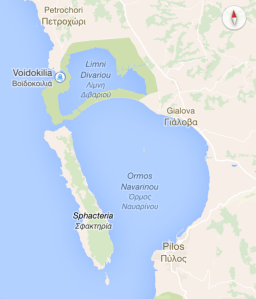

“Sandy Pylos”, as Homer describes it, is where Odysseus’ son Telemachus went to King Nestor’s court in search of his father. Overlooking a huge, enclosed bay, with blazing sandy beaches on much of its north and eastern edges, it is easy to be convinced by the descriptions in the Odyssey that this is the place. Sandy beaches are rare in the Peloponnese. (It is also where the British under Admiral Codrington, the French and the Russians annihilated the Ottoman Egyptian fleet at the Battle of Navarino in 1827).

At least since classical times, the town of Pylos has been at the south of the bay, near where it connects to the sea and close to the wrecks from the great sea battle. The Pylos to which Telemachus headed is now thought to be elsewhere, a Mycenaean settlement on a hilltop a little inland from the eastern shore of the bay, excavated from 1939. This is now confidently claimed to be Nestor’s Palace. I do not believe there is any direct evidence actually connecting it with the name Nestor, but it is indisputably an important Mycenaean site, with much for visitors to see. (We rented a car in Pylos for a couple of days).

Let’s assume that this is Homer’s Sandy Pylos – I certainly want to believe it. How accurate are the passages in the Odyssey? If this is Pylos, then Homer’s geography of the rest of the Peloponnese is wildly out; Bernard Knox, in his introduction to Robert Fagles’ translation of the Odyssey (8), says Homer displays “total ignorance of the geography of mainland Greece: his Telemachus and Pisistratus go from Pylos on the west coast to Sparta in a horse-drawn chariot over a formidable mountain barrier that had no road through in ancient times.” So at Pylos we find a reasonably recognisable place mixed with basic error, a useful lesson in not taking any set of descriptions literally.

Modern Pylos is a charming town, and we spent several nights there, encouraged by the fact that the yacht harbour was free, prompting a number of long term cruisers to use it as a base. (Like Kyparissia, our previous port of call, it seemed to be a failed commercial venture, left without a harbourmaster.)

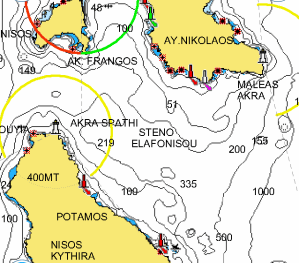

After visits to the great Venetian fortresses of Koroni and Methoni and to the modern town of Kalamata, my final Odyssey location before leaving the boat was the channel between the island of Kythira (or Cythera) and Cape Malea, the tip of the southernmost of the great fingers of land pointing down from the Peloponnese. It was there, while trying to turn north towards Ithaca, that Odysseus was blown west for nine days into a strange world of wonders and terrors.

We actually sailed to Capa Malea in gentle winds and calm seas, so only the text of our pilot book gave us any clues to its true nature, as a place of sudden violence. The book gives detailed instructions on the best bay to wait in bad weather, in the shelter of the little island of Elafonisos. Sometimes yachts wait for days to round the cape.

To the extent that there is any agreement about Homer, this part of the story is accepted as having been real, if only because the Cape would have been a notorious obstacle to navigation for anyone sailing in Greek waters in small boats, just as it is today; a storyteller would naturally be expected to include a reasonably accurate account of it when describing a voyage from the Aegean to the western side of Greece.

This seems particularly likely if Homer himself came from the Aegean, a sea of raiders and traders. While there are disputes about virtually everything in this field of study, and no conclusive evidence that Homer was one person rather than two, a collective or whatever, there does seem to be something of a modern consensus that the author (or authors) was based in the eastern Aegean. The island of Chios is a favourite for his home, or possibly near Smyrna on the coast of the nearby mainland, now Turkey.

If so, his descriptions of the Aegean and its fringes are likely to have been informed either by direct experience or from conversations with sailors, and would therefore be much more realistic than his accounts of places further away.

This is indeed the case: King Nestor’s description of the alternative routes from Troy to the Peloponnese (9) is about sensible passages recognisable on today’s charts, which has only been possible since the late 19th century when Troy itself was located by Schliemann and his collaborators. The closer to Chios, the more accurate.

The Ionian Sea would have been a long and dangerous voyage away from home for a bronze-age sailor; it is too demanding to expect that every detail of the descriptions of Ithaca and its surroundings is accurate and consistent, and fruitless to focus on minute analyses of the geographical significance of the precise wording of Homer’s descriptions.

Migration, trade and the Odyssey stories

Having waded through all these confusions – a jumble of places described with varying degrees of accuracy and stories and myths that have no real location in the world – I was grateful to find a book by Robin Lane Fox, Reader in Ancient History at the University of Oxford, (and also the revered gardening correspondent of the Financial Times). He puts the geography of the Odyssey’s stories in a framework of migration and trade routes that begins to make sense.

In Travelling Heroes (10), he shows how myths and tales from the lands east of the Mediterranean, many emanating from the area of modern Syria, migrated westwards as they were spread by traders and emigrants; the myths were adopted and adapted by newly-found communities in Greece, Italy and elsewhere, which assigned them more familiar locations closer to their new homes. The stories could shift geographically multiple times.

The idea that some fixed travel itinerary can be deduced for Odysseus begins to look ridiculous against that background. It is easier to read the book as a mixture of some real, often hazily remembered geography and events, and stories that have evolved in a way that detaches them from their origins – mythical or otherwise – and from the map, until they were fashioned many centuries later into a single narrative. This analysis of the Odyssey as a mixture of the imaginary and the real, with the real often shifted geographically, was developed in some detail by Strabo in his Geography two thousand years ago (7).

Searchers for Odysseus often pin their theories on the views of classical authors whose own contemporaries strongly disputed their accuracy. Referring to the ancient business of fitting real places to Odyssey stories, Knox says (11) “This wild goose chase had begun already in the ancient world, as we know from the brusque dismissal of such identifications from the great Alexandrian geographer Eratosthenes,” whose pithy put down was that you could chart Odysseus’ course when you found the bag into which Aeolus sewed the winds (7). (This line is known only from a quotation in the Geography, and is actually taken from a long passage in which Strabo attempts to demolish Eratisthenes’ claim that the Odyssey stories are entirely mythical). Knox adds that this has “not deterred modern scholars and amateurs from guesses running from the possible – Charybdis as a mythical personification of whirlpools in the straits between Sicily and the toe of the Italian boot – to the fantastic: Calypso’s island as Iceland”.

So where does this great dose of scepticism leave the sailor in the Mediterranean looking for an Odysseus story on which to peg a cruise? There are still enough plausibly genuine Homeric sites – whether real settings for an imaginary story or the locations of actual events from long ago, or both – for a splendid cruise: from the known location of Troy, along Nestor’s Aegean routes, perhaps taking in Homer’s possible home on Chios, to Cape Malea, round the Peloponnese to Pylos, and up into the Ionian. There you can make a pilgrimage to Ithaca and its excavations, or widen your search to Cephalonia and Levkas to explore the competing theories.

Anywhere else in the Mediterranean, if anyone tells you Odysseus was there, sit back in the cockpit with a large glass of red in hand, read Fagles’ wonderful translation of the Odyssey*, contemplate the wine-dark sea, and ignore them. As for Ithaca, for the moment I’m with the director on the argument.

Notes

(1) Ionian, Rod and Lucinda Heikell, Imray 2014. On the first cruise, we had Rod Heikell’s 2003 edition. The current one has added a summary of Bittlestone’s theory. To defend Rod and Lucinda Heikell against the director’s wrath, they don’t actually side with Dorpfeld and they seem to lean gently towards accepting the modern Ithaca, though the director would not appreciate their claim that there is little actual evidence of a Mycenaean kingdom there. The Odyssey connections of harbours and anchorages are recorded throughout this excellent pilot book. I wrote notes of the conversation with the director on the back of the Ionian chart as soon as I got back to the boat.

(2) It is apparently possible to translate the key phrase in Book III as “towards the west” rather than furthermost. The Odyssey, Everyman’s Library, translated by Robert Fitzgerald with an introduction by Seamus Heaney, 1992, postscript by the translator p467-8. Incidentally, Fitzgerald’s identification of Homer’s little island of Asteris as the modern Attako (p470-1) is mistaken, as a quick glance at the Imray chart of the central Ionian will show.

(3) Pausanias, Guide to Greece, Volume 2: Southern Greece, Penguin Classics, Translated by Peter Levi, introduction Page 2.

(4) Homer’s Readers: A Historical Introduction to the Iliad and the Odyssey, Newark, Del, 1981, Howard Clarke, quoted by Knox (see (7) below). Clarke says: “There have been some seventy theories proposed since Homer wrote the Odyssey, with locations bounded only by the North and South Poles and ranging within the inhabited world from Norway to South Africa and from the Canary Islands to the Sea of Azov.”

(5) Ulysses Found, Ernle Bradford, The Century Seafarers, first published 1964. His route followed conventional (and ancient) scholarly wisdom on the subject.

(6) The Ulysses Voyage, Sea Search for the Odyssey, Tim Severin, Hutchinson, 1987.

(7) Bittlestone and Knox (see (9) below) both quote Eratosthenes, c 285-194 BC: “You will find the scene of the wanderings of Odysseus when you find the cobbler who sewed up the bag of the winds.” Bittlestone of course spends much of his book attempting to demolish that view. The best read of all on this must surely be in Chapter 2 of Book 1 of Strabo’s Geography, written almost 2,000 years ago, where he counters Eratosthenes’ view by describing an Odyssey world that is instead part real, part imaginary.

(8) As supporting evidence, Bittlestone cites a passage in Strabo’s Geography, written almost exactly 2,000 years ago, stating that the isthmus leading from the main island to the western peninsular of Cephalonia was “so low lying that it is often submerged from sea to sea”. A thousand years earlier it was a true island, Bittlestone argues.

(9) The Odyssey, Translated by Robert Fagles, Introduction and notes by Bernard Knox, Penguin Classics, 1996. Introduction, p 26. He also says that Homer’s description of Ithaca “is so full of contradictions that many modern scholars have proposed Leucas (Levkas) or Cephallenia as the real home of Odysseus rather than the island that now bears the name”. On the other hand, “Nestor on the alternative routes from Troy across the Aegean sounds like an expert seaman.”

(10) Travelling Heroes, Greeks and their myths in the epic age of Homer, Robin Lane Fox, Penguin Books 2009.

(11) Fagles’ Odyssey, Introduction p25.* Update 2018 – Emily Wilson’s brand new translation, published by Norton, is proving just as enjoyable.

Postscript: It seems Homer never let the facts spoil a good story, as we used to say about newspaper colleagues who cut corners. Herodotus’ ‘Histories,’ in a gripping new translation by Tom Holland, has an alternative account of the background to the Trojan war that preceded the Odyssey, which throws some more light on how the Homeric stories may have evolved. Herodotus was told by Egyptian priests that the runaway lovers Helen and Paris were blown off course to Egypt by a storm, and weren’t at Troy at all during the siege. The ruler of Memphis expelled Paris from Egypt but kept Helen, eventually reuniting her with her husband Menelaus. Herodotus says (writing in the fifth century BC): “It seems to me that Homer picked up on the [Egyptian] story too, for while it did not lend itself as well to an epic tone as the plot-line he eventually used, he did demonstrate his awareness of it before setting it aside.”

The first great historian goes on to quote several passages from the Iliad and the Odyssey which he says are references to this Egyptian version. He adds “What all these passages clearly serve to demonstrate is that Homer was well aware that the wanderings of Paris had taken him to Egypt.” Herodotus says he had this version of the story “from the priests of Egypt – and speaking personally, I do not doubt their account as it relates to Helen.”

Apologies to classicists for whom Herodotus is basic raw material, but it took this excellent new translation to get me past the first few pages, which is as far as I got on a previous attempt.

Herodotus – The Histories. Penguin Classics, 2013, translated by Tom Holland with an introduction and notes by Paul Cartledge, p 152-156.

Dear Peter, can’t tell you how much I enjoyed reading this piece. Thank you for having taken the time and trouble. I will forward the link to our fellow crew members. I look forward to another opportunity to cruise together – Martin

Peter, This is a very interesting and very sensible article on this old question. I visited Cephalonia this past spring and wish I had been with you on the Martin voyage to have had the benefit of your common sense views on the matter.

Best wishes,

Mike Walker

Dear Sailor, This fine article covers the waters of my movie Iliadizzy, The Iliad & Odyssey, 21C. I wanted to learn the tides at Vathi where Odysseus finally lands in my tale. Seems tides are low. Penelope in my epic sings the hero’s voyage back to her, although in fairness to my gender I do not credit w/Samuel Butler that this voyage was written by a woman. If you wish to see selects from my movie, I would be honored. Thanks for your travel log. Y T S A