These are the posts from our 2024 cruise, with the order reversed to start with our planning a year ago.

3 Oct 2023

Just realised with a bit of a shock that at the weekend I will be the same age as Spring Fever’s last proprietor when he gave up sailing because he was getting on a bit, and sold the boat to us.

That was nearly 15 years ago. I thought of retitling this blog The Oldie Sailor, but Richard Ingrams, the Private Eye Editor who founded The Oldie magazine for irascible ageing writers, might have something to say about that.

Judging by the age profile at Cruising Association events and at the Southampton Boat Show, we are not alone, and the number of older sailors is growing rather fast.

The best way to celebrate a big birthday that comes towards the end of the season is not just to plan an interesting cruise next year, which will be a pleasure to think about as the nights lengthen. It’s also to hope that somebody gives me a lovely dry, warm waterproof offshore jacket to replace my old one, which is falling apart….

Oldie plans

10 December 2023

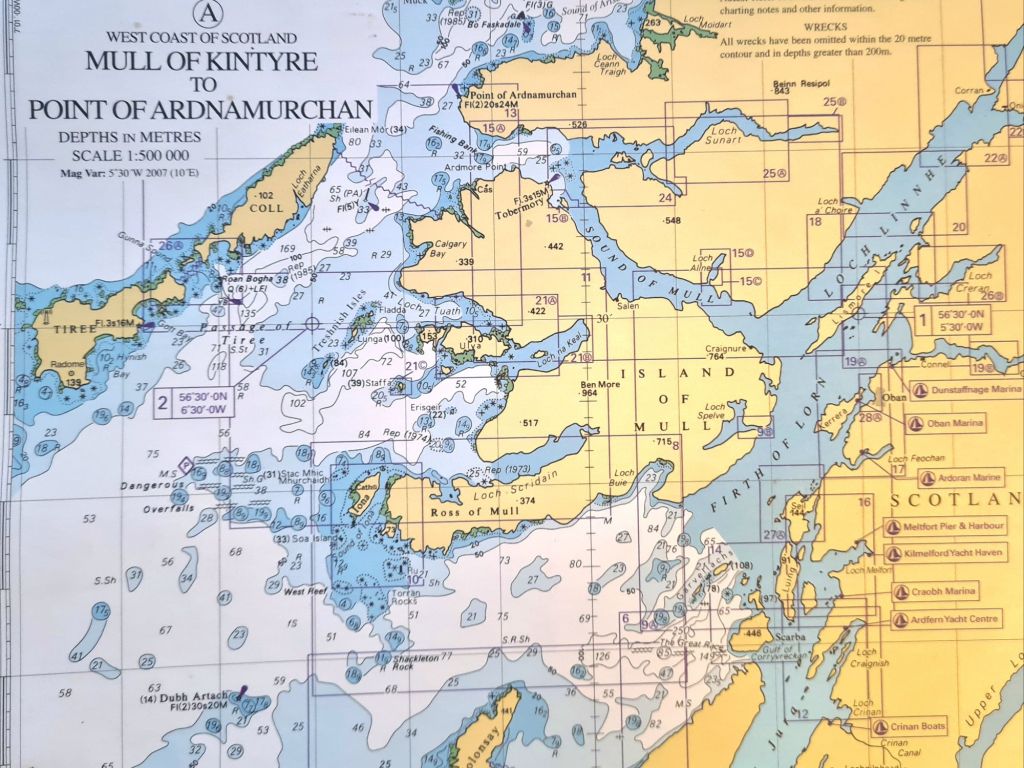

Here’s what we’ve been thinking about for next year’s cruise: a third round-the-British-Isles voyage, at an even more leisurely pace than before, giving time to explore places we missed and revisit some of the most memorable.

Part of the attraction is that England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland take on an entirely different character when toured by sea. I was reminded of that by re-reading Jonathan Raban’s Coasting from 40 years ago, in which he seemed to discover a new country by touring Britain in a small boat.

We’ve actually toyed in recent years with going south to the Mediterranean (which then got annoyingly complicated with Brexit and VAT) or east to the Baltic. But the allure of the 2,000 or so miles round Britain and Ireland (depending how closely you follow the coastline) is that it includes some of the most beautiful cruising areas in Western Europe, especially in the North and West, and there are also a large number of easy to reach places where the boat can be left. It’s then simple to catch a train or a bus home at short notice, which makes planning easier and less rigid.

It’s actually a way of cruising described in many older sailing memoirs. If a contrary wind made progress too hard, then skipper and crew went home for a while. With tiny engines and sometimes none at all, they couldn’t pound stubbornly to windward under sail and power as we often do nowadays: they would instead hand the keys to a local boatman and head for the nearest railway station, returning in better weather.

The obvious disadvantage of the British Isles against going south is of course the variable weather and low temperature. But with flexibility of timings and transport rather than fixed dates for flights to and from other sailing destinations in Europe (unless you pay a fortune for last minute tickets) you can raise the chance of sailing in good weather. Even Scotland has the occasional heatwave!

An account of our first Round Britain cruise is in these links: 2007 in Pepper from Harwich via Ireland to Oban, and our passages back to Harwich via the Orkneys and east coast in 2008. For our 2012 cruise in Spring Fever – see this link: up the east coast then via the Caledonian Canal to Oban. The following year we wandered back to Cowes via the west of Ireland, doing a regular blog, often daily – here’s where the series of posts start, with our spring launch in Ardoran, near Oban. We now have a few winter months to work out next year’s route.

PS I got that lovely jacket I wanted for my 80th birthday.

Lazy sailing for oldies

30 Jan 2024

Tiredness is dangerous at sea, and it creeps up faster as we grow older, so we need to think hard about how best to avoid it. Having good equipment is obviously vital, but top of my list of priorities is not hardware but changing our attitude to the challenges of weather and sea. We must take the lazy option, and stay where we are if it looks too much like hard work out there.

We once bought a boat from a highly competent couple who said they had not been out in a Force 6 for 10 years, even though they spent three months a year afloat. They had the right idea: they were adapting their sailing to their age, and refusing to hurry to meet fixed schedules.

There was a time when the prospects of a long passage to windward or a fast ride downwind surfing from the tops of waves were exciting challenges.

I remember multiple occasions standing on the foredeck gybing a big spinnaker in strong winds, sometimes at a race turning mark with other boats fiercely jockeying for position. Changing a foresail on a plunging foredeck with seas breaking over the bow was a routine job.

All good to reminisce about now, but at my age they’re reminders of why we should not be going anywhere if the forecast is bad.

The racing spinnaker should stay in the garage and the asymmetric cruising chute should be reserved for fine weather. We usually sail with two to four people on board, two of whom and sometimes three are over 70. Athletics on the foredeck are out of the question, and so is racing (with the single exception for me of the annual Transadriatica on friend Martin’s boat).

If the forecast is bad, we should wait, or maybe leave the boat and catch a train home for a couple of weeks. There are extra costs in travel and mooring fees, sometimes in expensive places where we might only have been planning a stopover. That’s part of the price of keeping sailing.

There’s more about how to make offshore sailing feel less like hard work in this link and a detailed account of how we are updating our electronic chart equipment is here, for those with similar boats and similarly tight budgets.

Meanwhile, don’t forget entertainment for those long days spent waiting for the weather……

Ready to go

9 May 2024

Spring Fever is ready to launch, with the topsides polished, the bottom antifouled, the engine serviced and an overhaul of the electronics. She hasn’t looked as smart for quite a while.

We will be afloat from May 14, very late for us. We’ve given up our mooring in Cowes because we are going to Scotland for a year, and it has been cheaper to stay ashore until we are ready to go than to pay as a visitor.

The rigging and the Furlex will be checked by the professionals at Spencers once we’re afloat, and then we’ll head for the east coast, with a pause of several weeks at Woolverstone near Ipswich, because of other commitments.

Off we go – Cowes to Harwich

25 May 2024

Some people race non-stop round Britain. Others sail 2,000 miles in a frantic six weeks cruise over one summer. We left Cowes a few days ago and won’t be back before autumn 2025. With so much to see, what’s the point of rushing?

Our home port looked attractive in the dawn light as we left the harbour at 0445 on a still, calm morning, with our destination Harwich Harbour, and then up the River Orwell to Woolverstone.

This passage eastwards up Channel from the Solent is always navigationally satisfying, because the tidal patterns work very much in the boat’s favour, and make it faster heading east than for a boat going back westwards.

From Beachy Head onwards, you can ride the top of the tidal wave as it runs up the channel, so that the eastward current stays with the boat as far as North Foreland, the headland at the entrance to the Thames Estuary. Depending on the speed of the boat and its position when the tide turns east, the current may be favourable for as long as 11 hours.

The Thames Estuary is fascinating, though it needs a bit of imagination and a chart to see why, because the surrounding land mostly looks low and featureless from the sea. The estuary is packed with long finger-like sandbanks pointing mainly north-eastwards, so that crossing it in a small boat is like threading through invisible islands, finding short cuts, guided by a large number of buoys and beacons.

On this trip our first few hours after we reached the estuary were at night, in good visibility. There were lights everywhere: red, white, yellow and green navigation lights on buoys and beacons; lights on ships following the deep water channels; other ships were anchored and lit up like Christmas trees, because the big ones are obliged to keep on all their deck lights so they can’t be missed. For a while there was moonlight, and then great arrays of white and red lights marking the wind farms.

The shortest route crossing to Harwich is through the huge Thames Array windfarm, where they have helpfully marked a channel between the towers with the red and white buoys that show safe water. The giant rotors are set so that at their lowest point they are about twice the height of Spring Fever’s mast. There are exclusion zones round the towers, but who would want to get close anyway?

The estuary is always busy with shipping, but it’s less of a worry than when crossing the English Channel, because in most places it is easy to get to somewhere they can’t reach. The estuary channels are relatively narrow and, if in doubt, the solution is to nip over into shallow water on the edge of a bank, where a deep-draught vessel would run aground. With a depth sounder and a good chart, it’s also straightforward to do the same in the estuary in poor visibility and, in bad weather, the lee side of a bank gives some protection from the waves. The collision risk is more from fishing boats and other small vessels.

We had plenty of time to relax and think about these issues, because from the start the sea was flat and the wind was light and variable. We motor-sailed with just the mainsail, because no breeze appeared until we reached North Foreland and the Thames Estuary; when it did arrive it was a light Force 2 to 3 from the north, more or less dead ahead. A purist might have enjoyed spending 20 hours crossing the 40 miles to Harwich under sail in light headwinds, but not us. We ended up motorsailing the entire distance from Cowes.

That gave us plenty of rest, thrummed to sleep off watch by the steady noise of our 30HP diesel. We were still fresh enough to go straight on past Ramsgate instead of pausing there for a while, to finish the whole 170 mile passage in one go.

We’ll be staying at Woolverstone for a while, because because there are other commitments to fulfill, not least crewing in the Transadriatica from Venice to Novigrad and back to Venice, which is in June. And anyway, this is meant to be a slow voyage round Britain (though in what’s actually a rather fast boat for its size)….

Ipswich to Whitby

Jun 24 2024

Light winds again, just like our passage up the Channel. In the last couple of days, we’ve probably beaten all our past records for motor sailing.

We left Woolverstone, passed Pin Mill in a calm and headed down the Orwell, finding wind eventually for about half the first leg. It was a bright and sunny 40 miles from Harwich to Lowestoft along the low-lying but beautiful Suffolk coast. With a near-spring tide carrying us along, Spring Fever reached 9 knots over the ground at times as we passed Aldeburgh and Southwold.

It was more exciting than we bargained for at Lowestoft. We arrived just as a stream of fast catamaran workboats surged back into the harbour for the night from the wind farms and gas rigs, roaring past us as we approached the entrance – they must have been late for their tea. To complicate things the harbourmaster warned us on the radio that a large dredger was working just inside.

We stayed overnight in the Royal Norfolk and Suffolk Yacht Club marina, and dined in the club restaurant.

Next morning we set off for Whitby, a 150 mile overnight passage. There was almost no wind and a flat sea as we threaded our way between wind farms and gas rigs, the first few hours helped by a strong tide along the Norfolk coast.

The sheer scale of electrical and gas installations off the Norfolk and Lincolnshire coasts was impressive, with new windfarms still being constructed, service vessels rushing around and cranes mounted on big jack up rigs. These are floating platforms with extendable legs which are pushed down to the seabed to stabilise them. They lift heavy items such as the enormous rotor blades.

During the short midsummer night, the sea was lit by a full moon, with hundreds of red and white lights around us from wind farms and gas rigs. A faint glimmer from the sun stayed on the horizon all night, gradually shifting from north-west where it set to north-east where it would reappear.

We passed Flamborough Head in bright sunshine, and approached Whitby Harbour carefully: the south-going flood tide we had at the time could push boats in the direction of a rocky ledge that runs out from the south side of the entrance.

Whitby to Peterhead

July 1 2024

After leaving Whitby, we had more light winds on the Yorkshire and Northumberland coasts as far as Amble in Northumberland. However, we arrived just before the first strong winds of the cruise – too strong, in fact, because they kept us there several days.

It was no penance, because the countryside is beautiful and we found plenty to do. Warkworth castle is well worth visiting, and there is a lovely coastal path to the seaside village of Alnmouth, with a frequent bus back to Amble.

After losing three days to strong winds, we had to abandon plans to anchor for a while by the Farne Island bird reserve and then to spend a night or two at Holy Island.

We went straight on to Scotland and into the first port across the border, Eyemouth. This has an entrance close to a beach which can’t be seen until the boat is almost upon it – nerve wracking for the first time but this was our third visit.

We stayed one night, and left early for Arbroath, a town the other side of the Firth of Forth, sailing gently for most of the passage until the wind began to die 10 miles from our destination. Arbroath is where the smokies come from – haddock, smoked whole, ungutted.

Our passage was finely timed: Arbroath has a gate that opens either side of high tide, and because it was neaps it was for less than an hour that evening. We had got it just right.

Then we changed our minds: with some doubtful weather looming in a day or two and a peaceful night forecast, we decided to change course and head another 65 miles up the coast to Peterhead, to make some more ground before the unpleasantness arrived.

Peterhead to Wick

July 6 2024

The 75 miles across the Moray Firth from Peterhead to Wick was a reminder of how long the Nortb Sea has been a source of energy wealth. We passed close to a huge deep-water wind farm and near another big one under construction.

Close by there was an old oilfield from 1980, called Beatrice, which was exhausted and shut down 7 years ago. Nearby Captain, a small field discovered in 1977, is still operating.

Some new oilfields are still being developed, but north sea oil seems to be following the coal industry it replaced into oblivion, as the old giant fields run down. Jobs are already being lost in Scotland.

The wind turbines we saw are mounted on steel structures a bit like oil platforms, and are in 150 feet of water, very different from those perched on sandbanks in the south. As it happened, we only glimpsed the vanes in the murk as we passed, because it was a windy, rainy day.

The wind was mainly west so we scooted along on a broad reach, working hard, with the main double-reefed, and arrived in a wet Wick in late afternoon.

Wick is just south of John O’Groats and Duncansby Head – not quite the most northerly mainland town, which is nearby Thurso. There is an excellent small marina, where a staff member was waiting on a finger pontoon to welcome us, after we called the harbour master as we approached.

The marina is very sheltered, reached through the outer breakwater into the main harbour, then through a narrow entrance to an inner harbour, and through an even narrower entrance to the innermost harbour – no swell can get at you there.

There’s a good shower block, supermarkets in town and an excellent Maltese restaurant called the Printers’ Rest run by a Scottish-Maltese family.

Pentland Firth to Orkney

July 6 2024

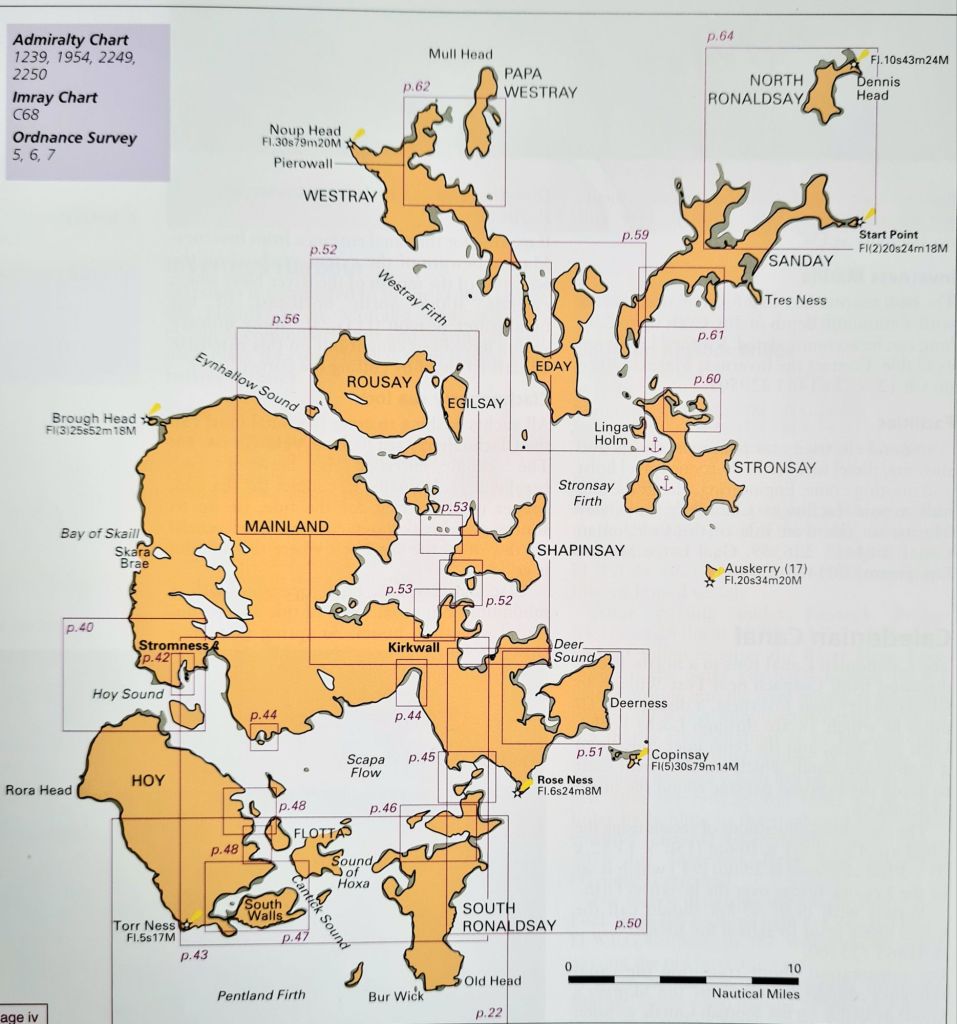

The next leg from Wick to Kirkwall in Orkney required careful preparation, because we needed to cross close to the Eastern end of the notorious Pentland Firth. This has ferocious tides but, more seriously, is peppered with rocks and deep underwater reefs that create enormous turbulence. Ships, even the navy, are wary of the Firth. In some conditions it can be deadly for small craft.

The pilot book says that passing through Pentland Firth from West to East, going with the tide of course because there’s no other option, is straightforward, and should give little trouble. Going the other way, westwards, is a completely different story and can be too dangerous to attempt in strong winds and tides. The layout of the rocks and reefs creates a chaotic and dangerous sea almost all the way across from the mainland to Orkney, especially with a strong west wind blowing against the tide. The most dangerous part of this wild turbulence has its own sinisterly inappropriate name: the Merry Men of Mey.

In fact, we had no need to actually go through the Pentland Firth because we planned to go to Kirkwall, the main Orkney town. That means crossing at the eastern end of the Firth and heading up the east side of the Orkney islands.

Timing is important, even so. With tides running at up to 9 knots and occasional patches marked as 12 knots (14mph) there’s a real risk of being pushed into the Firth if the crossing is attempted at the wrong time with a west-going tide. So we set off just as that was fading away and soon to turn. As the current grew, it would be pushing us away from the dangers. That meant another 5a.m. start.

As it happened, there was a good north-west breeze of up to Force 5 and we sailed so fast, double reefed, that the early start paid off. We crossed most of the difficult bit before the tide really got going.

We then headed up past the islands of South Ronaldsay, Burray and Copinsay, through Stronsay and Strapinsay Firths – what a lovely ring there is to the names – and into a narrow stretch with a fast tide and overfalls called The String.

We emerged from there into a wide but sheltered Firth overlooked by the main town of the islands, Kirkwall, where we moored on a pontoon at the marina.

It was a welcoming place, with the friendly harbourmaster waiting to take our lines. We had come less than 50 miles in cold, gloomy weather, but in terms of pilotage it had proved an interesting exercise.

To be sure we had the right crossing plan, from Wick we rang Mike Cooper, the Cruising Association’s honorary officer for the Orkneys, who was very helpful.

Kirkwall, Skara Brae and Ness of Brodgar

July 10 2024

Kirkwall to Cape Wrath and south again

July 10 2024

By great good fortune, the wind started coming from the east just as we were planning to head for the famous headland of Cape Wrath away to the West. What could have been a hard-working 90 mile battle into the wind to Cape Wrath and south to Kinlochbervie became an exhilarating down-wind ride.

First, we had to thread our way out from Kirkwall through passages between islands. The quickest exit to the West is through a shallow, narrow channel called Eynhallow Sound, where the tides run ferociously fast and cause mayhem in the water if they meet a swell and a wind coming from the west.

The advice is to time arrival at the Sound just before low tide when the flow has slowed and the turbulence has briefly subsided. That meant leaving Kirkwall at 5 a.m.

The day started windless and sunny, with tidal turbulence only visible on the glassy surface, often grabbing the boat sideways so we had to correct the course continually.

We went through Eynhallow Sound in equally calm conditions at slack tide, where we met the first waves of a low north Atlantic swell. They reared up and rolled the boat as they met the last of the outgoing tide – a mild hint at what would happen with big swells and winds against a strong tide.

Once out at sea, we motored for the first few hours of a 16 hour passage until the wind gradually built up through Force 3 to Force 5. With the engine off, we were tearing along at 7 to 9 knots over the ground, helped much of the time by a west-going tide. We had the mainsail double reefed to ease steering. Later, the wind reached Force 6.

The Cape is so prominent we could see its outlines in the distance hours before we arrived. Wrath actually means turning point in Old Norse, but the cape is well known for angry seas, and sudden changes of weather. There’s not much between the north-west corner of Scotland and the Arctic. The cliffs as you approach the Cape from the North East are spectacular; the Cape itself was in sunlight as we rounded it.

The seas were big enough to make steering hard work as we passed the Cape and turned 15 miles south down the mountainous Sutherland coast towards the tiny fishing port of Kinlochbervie, the first safe harbour. The sun went, the cloud closed in, the wind gusted, and the last miles of the passage were hard work, with the rigging whistling.

We turned east across a deep bay to find the almost hidden entrance to Loch Inchard. Round a bend in Loch Inchard and out of sight till you are almost upon it, Kinlochbervie appeared at the head of a small and sheltered side loch.

It’s a fishing village with modern quays and warehouses that have seen more prosperous days. There are two good cafes and a shop, and a pontoon for visiting yachts where we moored after much the best sail we have had on this cruise.

.

Cruising down the West Coast – Kinlochbervie, Lochinver, Inverewe

July 13 2024

We’ve done our main delivery trip: after passing Cape Wrath, Spring Fever is now cruising among the lochs and islands of the west of Scotland on the way down to Oban, which will be the boat’s home for a year.

There are hundreds of anchorages and dozens of harbours, with shelter from any given wind direction always in reasonably easy reach. We’re no longer trying to maximise the sea miles every day and are looking instead at a less strenuous 30 to 50 miles a day.

We began in the North Minch, a sea area protected from the west by the outer Hebrides islands of Lewis and Harris, though even in calm weather swells still arrive from winds far-away in the north.

We arrived in Lochinver after a pleasant sail past the Handa Island bird reserve and the looming cliffs of Stoer Head.

Lochinver is an important fishing centre, with big wharves and warehouses. It’s also in a beautiful loch with the stunning backdrop of Suilven and surrounding mountains, which have featured in many a calendar and tourist brochure.

There is a hotel with a bar, a restaurant, a cafe, a chandlery and a leisure centre, as well as a small marina.

In Lochinver, we spoke to the owner of a ketch which had just been towed in by the lifeboat after the steering had broken. He made a Pan Pan urgency call, an alert to his problem rather than a Mayday call for help. But the Coastguard and the RNLI decided it was safer to fetch him in than leave him wallowing in the swells off Handa Island trying to make repairs.

Next day we left in the rain for Loch Ewe, after phoning the famous Inverewe gardens to check where to land in the dinghy for a visit. They confirmed the pilot book advice to anchor in a little bay called Camas Glas near their jetty.

They asked us to make sure we didn’t leave our dinghy where it could get in the way of launches if a cruise ship comes in! There was a modest-size cruise ship anchored in the deep part of the loch – a couple of hundred passengers maybe – so we were relieved to see in the morning that it had left.

Inverewe Gardens

July 13 2024

Loch Ewe to Kyle of Lochalsh

July 15 2024

After a gloomy, cloudy start from Loch Ewe, the sun came out as we turned past the headland of Rubha Reidh and headed south.

With a brisk Force 4 to 5 exactly behind us, we were creaming along under mainsail alone.

We sat back and enjoyed a fast run down the Inner Sound on a beautiful day. The mountains of Skye were off to starboard the whole time, looming above the smaller, lower islands of Rona and Raasay that flank its eastern shore.

On our other side we passed the entrances to Gareloch and Loch Torridon on the mainland, dodged east of the small Crowlin Islands, accompanied for a while by a dozen leaping porpoises, and then across the wide entrance to Loch Carron.

We turned east under the Skye Bridge, with 10 metres clearance above the mast, and spent the night moored at a pontoon in Kyle of Lochalsh. Supper was in a bar to watch the final of the European Cup.

The next morning we dropped off Anthony, who had been with us all the way from Ipswich.

Lochalsh, Canna and Tobermory

July 17 2024

After watching the European Cup final we stayed, in a not particularly cheerful mood, on the harbourmaster’s pontoon at Kyle of Lochalsh, just across from Skye.

Next morning there was some cleaning to do, because Loch Ewe mud from the chain and anchor had left sticky traces on the deck.

We left on a bright, sunny and unexpectedly warm morning, sailing down Loch Alsh to Kyke Rhea, the fiercely tidal narrows that separate Skye from the mainland.

And finally – Kerrera, Spring Fever’s home for a year

July 22 2024

We left Tobermory on a grey day, with wind blowing from dead ahead along the Sound of Mull and rain clouds chasing each other across the sky. It was a wet and blowy last 25 miles to our destination, the island of Kerrera on Oban Bay, where we’ve rented a mooring for a year.

Since we left Cowes, we’ve covered more than 1,100 sea miles in 31 days, according to the boat’s electronic log (its distance and speed measuring instrument), excluding the pause near Ipswich which allowed a diversion to Venice for the Transadriatica Race. Draw straight lines between ports of call and it would be just over 1,000 miles

Duart Castle, at the entrance to the Sound of Mull, looms through the rain as we pass.The laird of Duart was due to preside that day over Mull’s annual Highland Games

We kept a strict look out through the murk for ferries and saw several emerge. After crossing the Firth of Lorn, we crept round the edge of the narrow entrance to Oban Bay, as strongly advised by the harbourmaster. Oban is the main hub for the Caledonian MacBrayne network of ferries to the islands. They pop out suddenly from behind a hill as you enter from the other direction

Oban Bay is beautifully sheltered from all directions, protected by the long thin island of Kerrera, where we have rented a mooring.

We tied up in the rain to the sound of a pair of bagpipers, though sadly not heralding our triumphant arrival. Instead they were welcoming Sir Robin Knox-Johnston to a party in the marina restaurant for the crews of the Clipper Round the World yacht race, which he founded.

After crossing the Atlantic on the final long leg of the race, the 11 strong fleet was stopping in Oban for the first time in the race’s history, before heading off the following Sunday to the finish in Portsmouth. Sadly, it was race participants only, and other crews were not on the guest list.

The restaurant, we discovered the next evening, was excellent, with a short but interesting menu of fish, shellfish and venison, and a cheerful atmosphere, in keeping with the portrait at the entrance of Tim, the co-owner.

Next day we headed for Oban on the marina’s little ferry, to say farewell to Michael at the railway station and also to sample the delights of the best shellfish stall I know anywhere.

The stall sells perfectly cooked local mussels to eat standing up or on benches on the quayside. There were scallops, oysters, dressed crabs, langoustines, clams, lobsters, whelks, salmon poached and smoked – all local and cooked in the shed behind or sold raw

The oysters were the best I could remember in recent years, and the scallops, though pricey, were delicious. As for the crab, prawn and salmon sandwiches, they are perfect for lunch on the train to Glasgow from the station 100 metres away. They have more filling than bread. (I have to explain that my sampling was spread over three meals….)

The next day, Tony left by train clutching sandwiches, as Michael had the day before. I was to be on board for a couple more days to put Spring Fever on her permanent mooring once the previous occupant had left.

That meant I was there for the departure of the Clipper Fleet, which formed up for a follow-my-leader circular sail round the bay, then a sail past the crowds looking on from the town, then exit from the bay in line astern. The actual race start was just outside in the Firth of Lorn

Joining the challenge is not cheap. A single one of the 8 legs can set you back £6,000 to join, including a month’s crew training. The price may be why quite a lot of the crew we saw seemed to be well into middle age, perhaps in search of a break in which they can do something truly memorable before too late.

The publicity says some crew start as complete novices. Reading up on the race, especially a long article in the Guardian last year, there have been some pretty terrifying times for crews in past races, particularly in the southern ocean.

For some years the race had only one professionally qualified and experienced sailor on board, as skipper. Now there is a second professional. All but the skipper and deputy are paying customers, many with no more experience than the Clipper training month, so it’s brave of them.

Later that day, I took Spring Fever out to her mooring, tidied up, did a bit of relaxingly therapeutic canvas sewing (making a new outboard cover), and got the boat ready to leave till September, when we plan to be back on board.

The next morning, after 32 nights on board, I caught the ferry to Oban for the 3 hour train journey to Glasgow, along one of the most scenic routes in Britain, and then home.

Glossary

* Brigantine – two masts, only the forward one with square sails. * *Barque – three or more masts, two with square sails and the aftermost one with a fore and aft sail. Brig – two masts, both with square sails. Ship – three masts with square sails

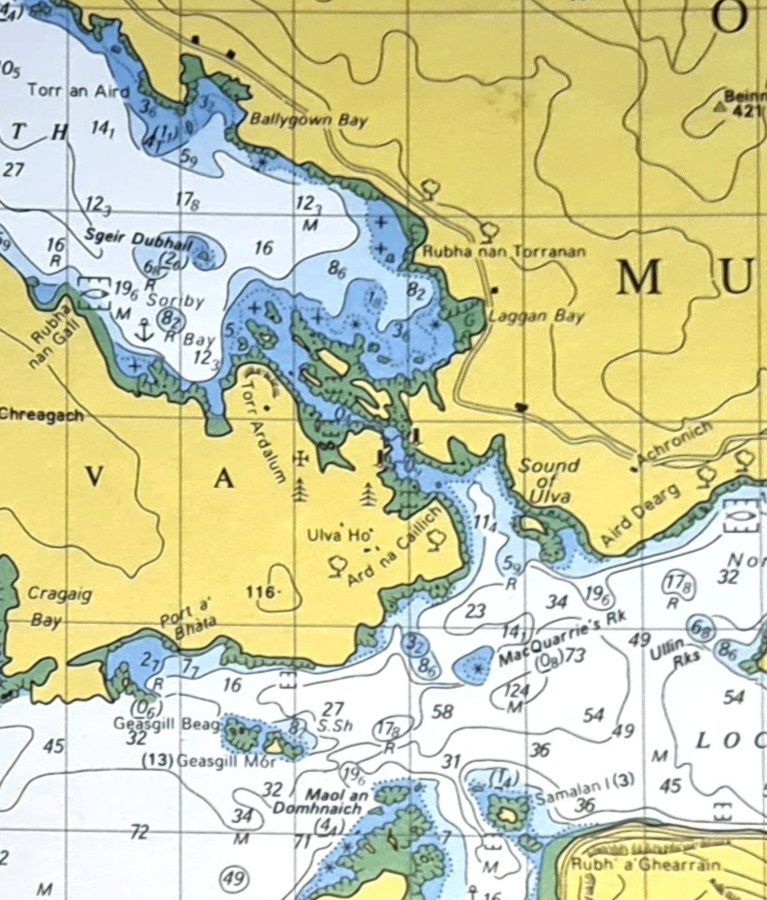

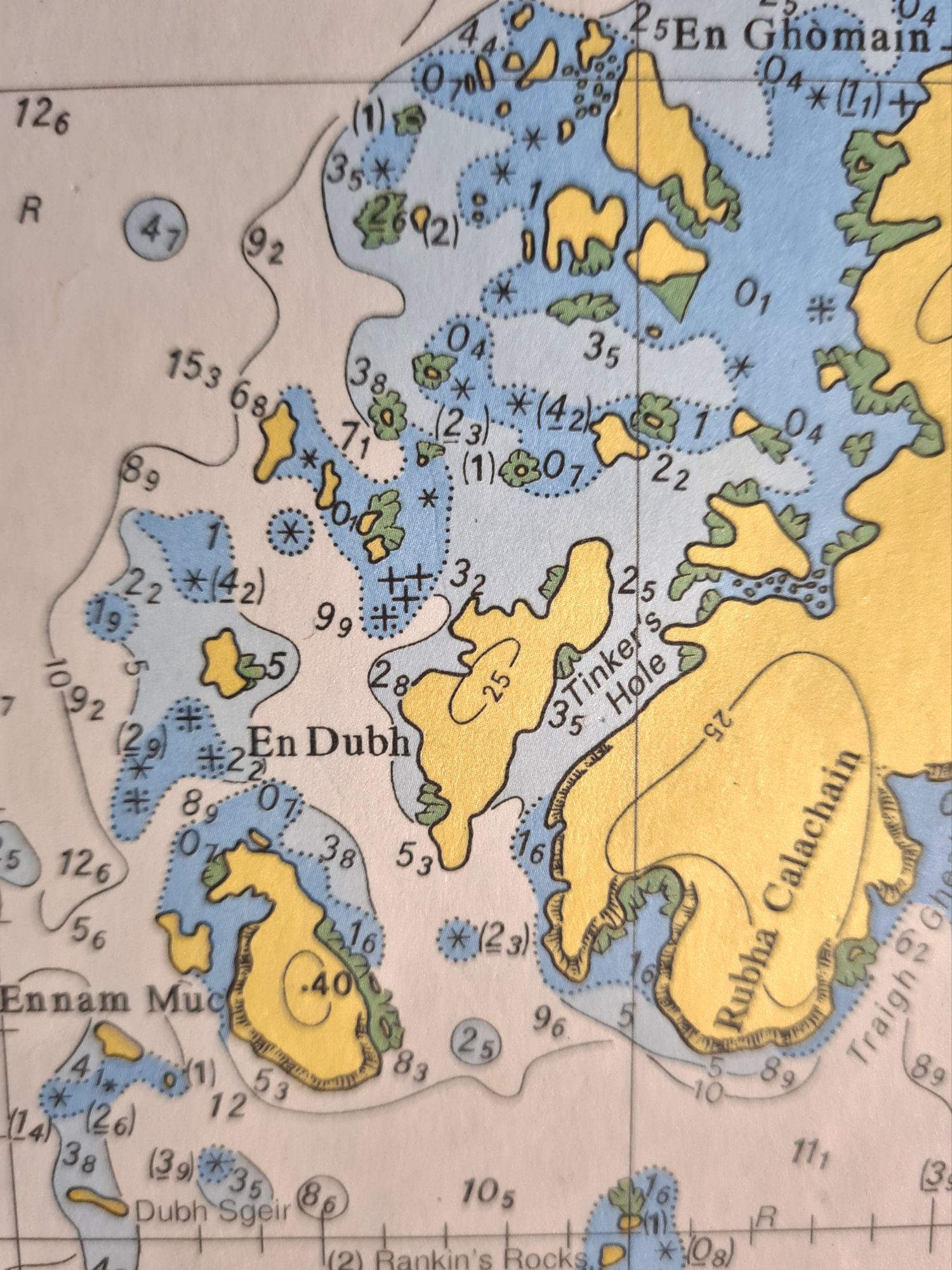

Autumn sun around Mull – Ulva, Coll, Tiree and Treshnish

Sept 28 2024

After waiting all summer for summer, it finally arrived in Scotland last week, with sun, light winds, and calm blue seas. We were back on the boat after a long break.

The wind was generally from the east, so it was a good time to see the little islands west of Mull – Treshnish, Ulva, Coll and Tiree, plus a night in beautiful Loch na Droma Buidhe and another in a sheltered gap in the rocks near Iona called Tinkers Hole. For this week, captioned photos tell the story.