Sometimes I wonder where the Royal Yachting Association has been for the last 10 years. I have just had an email from them saying “in the next ten years or so digital will become the dominant method of navigation”. In the real world of small boats, digital has been the dominant method of navigation for at least the last 10 years.

Continue reading “RYA navigators still last in the fleet”Tag: RYA

Just out – the new Pass Your Day Skipper

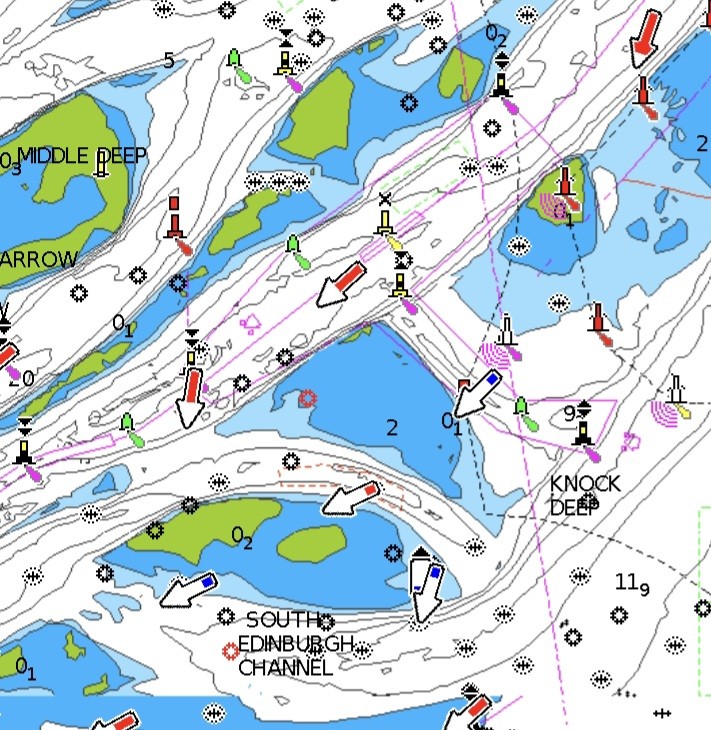

The new edition of Pass Your Day Skipper by David Fairhall and Peter Rodgers is now on sale. The book was originally by David but – at his invitation – I’ve expanded it and added lots of new material on electronic navigation, weather, and safety. The illustrations are by the famous sailing cartoonist Mike Peyton.

Peyton’s cartoons are still hilarious for any sailor, and most of the jokes are drawn from real-life incidents of a sort familiar to most of us. Anybody who’s been sailing for a while will have memories of their own mistakes, bad luck or cringe-worthy bad judgements: Peyton pins them all down.

The book is meant to be used as a crammer or revision text to study just before the exam, rather than as a detailed training course manual. It packs a lot of information into a slim volume that fits in a pocket. That means it can easily be consulted in the odd free moment, perhaps when travelling – and even for a last minute refresher on the way to the exam.

Pass Your Day Skipper is published by Adlard Coles, part of Bloomsbury, and costs £14.99. Look for the 7th edition with both authors’ names on the cover. Some websites still seem to offer David’s earlier editions at a cut price alongside the new one.

Pass Your Day Skipper is a companion book to Pass Your Yachtmaster, which I also updated and expanded for a new edition, published in 2021.

Admiralty gives in

The revolution has been postponed: the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office has delayed the phasing out of its Admiralty paper charts for four years, to 2030. This follows pressure from the Royal Yachting Association and others.

The argument against losing paper charts sooner is that adequate electronic alternatives for small craft – especially small commercial ones – will not be ready in time.

Continue reading “Admiralty gives in”RYA electronic chart training has missed the boat

The near-universal shift by small boat sailors from paper to electronic charts has left the Royal Yachting Association’s training courses floundering in recent years.

That was underlined when Admiralty, owned by the UK Hydrographic Office and one of the world’s gold standard official chart brands, said in July that it will stop selling paper charts altogether by the end of 2026.

Continue reading “RYA electronic chart training has missed the boat”January – RYA training upheaval, and ending an electronic chart nonsense

The small craft navigation conference in Cowes at the end of January heard that the RYA is finally promising to overhaul its outdated Day Skipper and Yachtmaster shore-based courses.

The conference was also told that there is to be a concerted attempt to abolish that annoying legal disclaimer on all our electronic charts that they are “not for navigation.” As soon as we switch on a pop-up appears with this message, often with a line underneath saying that only paper charts must be used, which of course almost everybody ignores.

Continue reading “January – RYA training upheaval, and ending an electronic chart nonsense”…and a phone to steer her by

Mobiles have had a bad press as navigational tools, but if I were forced to choose one single piece of electronics to take to sea it would be my phone. That’s not a popular view among professionals.

Instructors, coastguards and rescue services learn of many cases where boat owners, especially of powerful motor yachts and RIBs, set off for the open sea with nothing beyond a chart app on a mobile phone, and no knowledge of the underlying skills needed to navigate safely. For the Royal Yachting Association, mobiles are well down the list of recommended priorities, because of the risk that they will be used badly. Textbooks give stern warnings that you must not use them for navigation.

Continue reading “…and a phone to steer her by”Yachtmaster book out

The new, updated and expanded edition of Pass Your Yachtmaster is in the bookshops. It’s the best primer around for the RYA sailing qualification, and the only one with jokes – the serious stuff by David Fairhall and myself is leavened with lots of hilarious cartoons about sailing by the late Mike Peyton.

There’s a new chapter on electronic charts and fresh material on weather forecasting, safety equipment and other aspects of sailing offshore that have been changing in recent years as the technology improves.

Continue reading “Yachtmaster book out”Back to the future – electronics on board

I was intrigued by the equipment list below, which is more than three decades old, because it was a reminder of how long we have been arguing about the risks and rewards of electronic navigation. I found the list in some old files I was checking last year for the sixth edition of Pass Your Yachtmaster by David Fairhall and Mike Peyton, which I was commissioned to update by Adlard Coles*.

The list was part of an article I produced for the Guardian newspaper about electronics for small boat navigation, under the headline ‘And a satellite to steer her by’, researched by talking to manufacturers due to appear at that year’s London Boat Show. I had forgotten all about it.

Continue reading “Back to the future – electronics on board”December – checking proofs

With the new lockdown – boat and our home both in the highest tier of antivirus restrictions – winter sailing plans are off for the moment.

So the only boating thing getting done here is proof correcting for the new edition of Pass Your Yachtmaster, by David Fairhall and the late Mike Peyton, the cartoonist.

It involved writing a lot more new material than I expected – or perhaps I should have realised, given the speed at which electronic navigation, marine communications, emergency location, search and rescue and numerical weather forecasting have developed during the 38 years the little book has been in print.

Continue reading “December – checking proofs”New Brexit chaos for yachts

Just when most yacht owners thought they had understood the impact of Brexit, the government has changed the rules on Value Added Tax, with expensive consequences for some.

Last year there were assurances that, after Brexit, a yacht that has been away from the UK on a long term cruise, typically a few years in the Mediterranean, would not have to pay VAT on returning.

Now it looks as if many will have to pay up, even if the boat was bought VAT-paid in the UK before it left – in other words, owners could find themselves paying VAT twice on the same boat. The second charge would be based on its market value at the time of its return.

Needless to say, cruising yacht forums are full of anger and anxiety, though this is not an issue that will get much sympathy anywhere else because yacht owners are not exactly an under privileged minority.

However, many are far from rich, living aboard on tight budgets for much of the year, often after retirement – ‘fulfilling their dreams’ as the yachting magazines love to put it – a far cry from the superyacht owners everybody hates (who in any case probably arrange their affairs so they do not pay European or UK VAT). And while it is very much a minority problem, how many other much more important parts of the economy are being hit by similar administrative chaos 10 weeks ahead of final departure from the EU?

Both the Royal Yachting Association and the Cruising Association are rather desperately seeking clarity from the government. The Treasury’s position seems to be that under EU rules we already charge VAT on a returning yacht after an absence of more than 3 years. It has decided this will continue to be part of the UK rulebook after Brexit.

But until now the practice has been to suspend the rule in many cases, by exempting private yachts that come back after more than 3 years, as long as they are under the same ownership and have had no substantial upgrades (eg a new engine). In these circumstances, the VAT charge has not been levied. The latest indications are that this concession may go.

Just as alarming for many people, the government has changed the point at which the clock starts on the 3 VAT-free years. Last year the RYA was told that a boat currently kept in an EU-27 country such as France or Greece would be treated as if it had left the UK at the point the UK itself finally leaves the EU ie at the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020. That would give a full 3 years to get back.

Now departure has been redefined as the point at which the boat physically left the UK. Any boat already kept abroad for more than 3 years will be liable to VAT if it returns to the UK after 1 January 2021. This led to howls of protest from the RYA and a promise that there would be an extra year – but no clarity about what that meant.

Would it allow a yacht that has already been abroad more than 3 years another year up to the end of 2021 to come home VAT free? Or would it just add one year to the 3 year grace period, so a yacht that has been away 4 years or less will not pay VAT after 1 January next year, but one that has already been away 4 years and a month will pay?

There’s another set of EU rules that make this even more onerous, if the UK imports them into its own post-Brexit system after we leave, as it seems to be doing with the 3 year rule.

Currently, as long as the importer of a yacht is not an EU resident, the yacht can be temporarily imported for up to 18 months without paying VAT. But if the importer is an EU resident, VAT becomes payable on arrival. (Nationality of the importer and registration country of the yacht are irrelevant – it is the country of tax residence of the importer that matters).

In the past, the UK has taken a tough line on this, with no grace period, though there has been at least one exception among EU countries – Greece in the past certainly allowed a month. If the rule is kept by the UK after Brexit, and applied strictly, it would be risky for a UK resident yacht owner to call in for a day at home in a yacht that has been abroad more than 3 years. The VAT would be chargeable immediately.

The rule seems to be aimed at stopping UK residents keeping their yachts VAT-free in tax havens such as the Channel Islands but using them in the UK – an obvious tax loophole if it were left open.

In fact Spring Fever was first registered in Guernsey in 1988. We have the VAT certificate to prove it was paid when the boat was imported into the UK a few years later, a vital document we guard carefully, especially in these new circumstances. With the first owner on the documentation shown as being a Guernsey resident, we may well be asked to prove VAT has been paid.

Battles over flares

In one corner, the Royal Yachting Association, declaring pyrotechnic flares are obsolete. In the other, the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency, pointedly renewing for another 2 years its ruling that flares are mandatory under the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convention, though softening it a little round the edges.

What does it actually mean for a typical small yacht? The crucial issue here is that SOLAS distress signals are only a legal obligation for yachts above 13.7 m or on smaller craft licensed for commercial use, including sail training. They must carry flares. This means if you charter a yacht, it has to have them. The RYA has, however, won a dispensation allowing private yachts from 13.7 to 24 metres to at least dispense with parachute rockets, easily the least useful and most hazardous in use of the flares. Continue reading “Battles over flares”

Hard Brexit and boat VAT – Treasury response

The Treasury has finally decided that if a yacht is in the European Union on Brexit day, it will not be liable for VAT if it is brought back to the UK later.

As reported before, the Commission said recently that British yachts would lose their EU VAT-paid status unless they were in the EU on the day of a hard Brexit.

If they were in the UK they would no longer have the status of union goods and would be liable for VAT on visiting the EU, so the best they could do would be to apply for temporary importation for up to 18 months. Continue reading “Hard Brexit and boat VAT – Treasury response”

Brexit petition.

Yacht owners are a tiny and unimportant issue in the big Brexit scheme of things and I certainly did not sign the petition to Parliament – link below – because of irritations over the treatment of boats and sailors.

Signatures were over a million last time I looked, and still rising so rapidly that the website kept stalling. Persevere! [6 million was the final tally].

Bang goes our EU status

It has now been confirmed that we will lose our boat’s VAT-paid status in Europe on Brexit day, leaving us with only the possibility of a temporary importation licence for up to 18 months.

Only British boats actually kept in the EU on that day will be treated as if the VAT paid on them in the UK is still European VAT. If they are in the UK on Brexit day, then they lose that ‘union goods’ status and can only apply for temporary importation.

Brexit and our boat

We’ve been looking into the impact of Brexit on our sailing, on the assumption that at some point we will be treated as a third country, just like US and Canadian sailors who cross the Atlantic to visit the EU. If there is a hard Brexit at the end of March, this could all be upon us next season. The result is likely to be a long term increase in paperwork and bureaucracy and a permanent annoyance for British yacht owners.

Even as EU members we have not been bureaucracy free. Because the UK is outside the Schengen zone, we have been obliged in theory to show our passports on arrival, though some Schengen countries such as France often do not bother to enforce passport checks on yachts. (That might be changing, because in July, for the first time in many years, we were boarded on a mooring by French customs officers in a RIB, whose only interest was in our passports).